A New Environmental Ethic

One of the most sustaining and important notions from the 70s was the idea that we should protect the Earth. It’s been argued that more than the first Earth Day in 1970, the key catalyst of our environmental activism was actually the sight of the Cuyahoga River fire just a year before. The flaming Cuyahoga sparked wide-ranging reforms, including the passage of the Clean Water Act and the creation of federal and state environmental protection agencies.

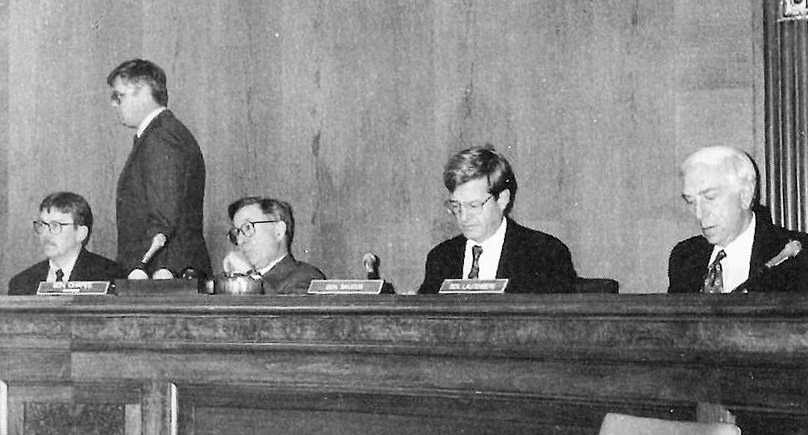

Although still in its infancy at the time, the Association of Metropolitan Sewerage Agencies (AMSA) had already become a “go-to” source of information and counsel for the federal government. The Federal Water Pollution Control Act was one of the first examples of how AMSA helped to shape major legislation. With the enactment of the Federal Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, the U.S. had a new law for ensuring its waterways were protected. Today, we refer to this statute as the Clean Water Act.

The Federal Water Pollution Control Act was one of the first examples of how AMSA helped to shape major legislation.

With AMSA’s urging, the final law established a federal construction grants program that helped provide financial assistance to larger municipalities to meet the law’s new national mandates. This program not only provided important investments for those communities that had begun construction of facilities under the previous law, but it also established a key principle of the federal and local partnership that helped make the Clean Water Act so successful—local clean water utilities would upgrade to meet a new national standard for pollution reduction, and the federal government would help provide funds to achieve that goal. AMSA was critical in helping negotiate this win-win partnership, and it was the most significant achievement of AMSA in its early years.

Amending the Clean Water Act

The Clean Water Act of 1972 successfully established a national program of investment in and regulation of our waterways, but it was still not fully solving the nation's water pollution problems. There were still too many challenges, and AMSA members would play a critical role, conferring with members of Congress to develop amendments. The eventual legislation, the Clean Water Act amendments of 1977, included a new five-year authorization of more than $26 billion for municipal construction grants, major changes in the states' role in the construction program, an extension of the municipal deadline, and an added push toward innovative technologies. The passage of the 1977 amendments solidified AMSA’s role in influencing federal clean water law and policy.

Financing Clean Water

As the 70s free love movement gave way to a new conservatism in the 80s, President Reagan entered the White House on a platform of reducing government size and reach. As part of this agenda, the 80s proved to be a transitional time for public clean water utilities, with the phase out of funding for the construction grants program and the emergence of a new Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) program, established by Congress in the Water Quality Act of 1987 and becoming effective in 1990.

Since its start, the CWSRF has surpassed $126 billion in cumulative assistance and continues to grow today. AMSA was instrumental in ensuring this funding continued through the years. Despite the success of the CWSRF, however, the shift in the 80s from a federal grants program to a federal loan program marked a fundamental shift in the clean water partnership between local governments and the federal government.

AMSA continued to build its value for the sector with more of a focus on developing financing strategies for capital projects and increasing its visibility as a national leader in environmental management, further enhancing its publications such as “The Cost of Clean,” its Financial Survey, and the AMSA Index of Service Charges, which provided the first national comparison of service charges for members.

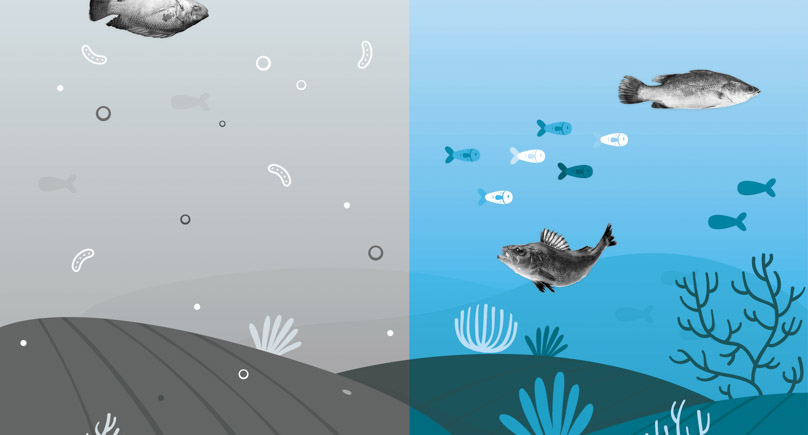

By 1995, toxics and pollutants were at their lowest levels in the nation’s waterways. Rivers and lakes that had been on the brink of biological extinction were now teeming with life.

The One-Water Approach

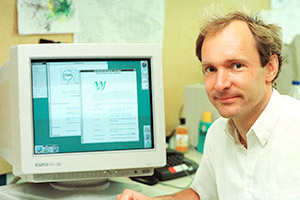

The brash boldness of the 80s swung back to slightly more mellow 90s. As the Cold War thawed, the 90s brought incredible advances in technology, particularly in the medical field such as the first gene therapy trial. And—thanks to clean water utilities—by 1995, toxics and pollutants were at their lowest levels in the nation’s waterways. Rivers and lakes that had been on the brink of biological extinction were now teeming with life. AMSA has continued to play an integral role in the reauthorization of the Clean Water Act and in EPA’s implementation of Clean Water Act programs, most notably the biosolids beneficial use program and the landmark National Combined Sewer Overflow Control Policy (NCSOCP), which gave municipalities both the clear direction and the flexibility they needed to effectively control sewer overflows at a significant savings. The eventual codification of the policy into the Clean Water Act put the full force of law behind its essential components and assured that the policy would not be arbitrarily amended or altered without significant review. AMSA also had considerable influence in pushing forward the notion of comprehensive watershed management as the most effective way to address watershed challenges and was already working to advance “watershed-focused” legislation in the early 90s. For example, by the late 90s, Atlanta, Georgia began planning a comprehensive watershed management approach, and in the early part of the 2000s, the city had combined the resources and talents of several of its teams into a unified Department of Watershed Management. This effort fostered a coordinated approach to effectively manage water, wastewater, and stormwater under one umbrella—a one-water approach.

Atlanta, Georgia combined several of its teams into a unified Department of Watershed Management to effectively manage water, wastewater, and stormwater under one umbrella.