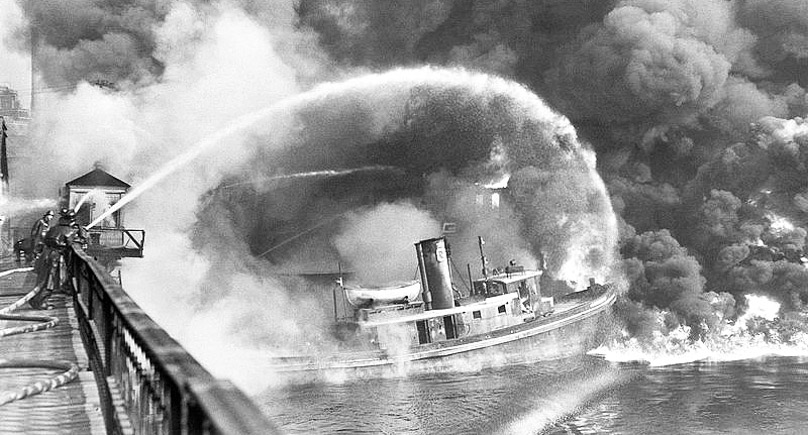

America wasn’t always mindful of the power or importance of clean water, nor were the utilities and people that provide it. In fact, prior to the Clean Water Act, most cities viewed their waterways as nothing more than a pathway for shipping goods and people between cities. The prevailing philosophy of the time was “the solution to pollution is dilution.” From colonial times through the post-World War II era, most communities treated their waterways as garbage dumps. We paid a tremendous price for this. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, water-borne diseases were rampant in the 19th century, including typhoid and cholera, which killed at least 50,000 Americans.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, water-borne diseases were rampant in the 19th century, including typhoid and cholera, which killed at least 50,000 Americans.

In the post-World War II period, communities began to focus on their polluted waters. Charleston, South Carolina as one of America’s earliest cities to start dealing with the issue. Charleston’s harbor waters were too polluted for swimming, and shell fishing was banned. By 1965, plans were announced for a program that would include a treatment plant. The new system was permitted for operation in 1970, just as state legislation was passed prohibiting dumping untreated sewage into the harbor.

Cities had the knowledge and people to address the problem, but they struggled to get the funds to build better treatment and didn’t have the regulatory framework they needed to really compel investments in the infrastructure. As a result, the very agencies at the core of the solution that were helping to clean America’s waterways felt as though federal regulators saw them as the core problem, and this did not sit right with many of them.

The Start of a Solution

More than two years before the passage of the Clean Water Act, wastewater utilities around the nation were being proactive, coalescing around the need for a coordinated effort to control water pollution. The earliest of these convenings can be traced back to Seattle, Washington, where the late Charles V. Gibbs, executive director of the Municipality of Metropolitan Seattle at the time, was confronting the sometimes conflicting direction on water pollution control coming from Congress and the Administration, direction that came with little or no federal funding or grant assistance. And Gibbs along with other public clean water utility leaders from around the country rejected the notion that their agencies were entities to be regulated as opposed to utilities with the means and knowledge to work collaboratively with the federal government to solve the problem.

Grants from the Federal Water Pollution Control Administration went mainly to small agencies serving few people. In order to conform with the requirements of the law, large metropolitan sewerage agencies had to use mostly local funds for building or improving their facilities. Then, in 1969, Congress began considering a bill that would provide substantial construction grants to sewerage agencies for future facilities and little or nothing to those that already had used their own funds for this purpose.

Gibbs was one of the outspoken leaders who considered this pending legislation to be unjust to the larger agencies, and he made this known repeatedly with letters, telephone calls, and visits to Capitol Hill. By 1969, he recognized that other metropolitan clean water agencies were having similar problems. He wondered if leaders from a number of these agencies spoke to Congress together with one voice, they might be heard.

Gibbs conducted outreach across the country and confirmed that many agencies like his were having trouble being heard in Washington. Representatives of 22 sewerage authorities convened later that year for the first meeting of what is now NACWA. It was Gibbs’ vision that the group would come away from this meeting with a plan for sewerage agencies to not just be heard but to also successfully influence federal legislation in a way that was more responsive to the needs of the nation's large cities and to better reflect the huge costs associated with the national clean water policies being considered. Who better to advise on such legislation, was their thinking, than the agencies at the front line implementing it?

Officially incorporated in 1970, NACWA represented 43 million people, or 22% of the total national population, with a mission to speak with one voice on water pollution control and to obtain federal financial aid while also providing valuable information to its members.

Out of this first meeting in 1969, the Association of Metropolitan Sewerage Agencies (AMSA), the precursor to NACWA, was born. Officially incorporated in 1970, it represented 43 million people, or 22% of the total national population, with a mission to speak with one voice on water pollution control and to obtain federal financial aid while also providing valuable information to its members. This coalescing of clean water agencies could not have happened at a more opportune time, as the country was on the verge of a nationwide movement—one that would recognize and, ultimately, support investments in clean water.